The AP on Black and Indigenous People

On June 19, 2020, the Associated Press announced that “Black” and "Indigenous” are the new norms when referring to people of African descent and the original inhabitants of a specific place, respectively.

2020 has been called “unprecedented,” which we can all agree is a polite euphemism for the less-polite expletives that we’re all privately thinking. The COVID-19 pandemic has been a gut-punch to life as we knew it. The senseless killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and others were on full display. And rather than finding time to connect with friends and family in the physical realm, many of us are grieving the loss of loved ones due to coronavirus.

Encouragingly, there have been some bright spots. If I haven’t said it before, let me say it now – we have some really amazing partners and clients! On a broader level, I’ve been encouraged by the collective awakening concerning racial discrimination. Even the keepers of good grammar at the Associated Press have joined the cause.

On June 19 (known among African Americans as Juneteenth), the Associated Press announced that “black people” are now officially “Black people.” There’s more: “indigenous people” are now “Indigenous,” when referring to the original inhabitants of a specific place.

The AP writes, “These changes align with long-standing capitalization of other racial and ethnic identifiers such as Latino, Asian American and Native American. Our discussions on style and language consider many points, including the need to be inclusive and respectful in our storytelling and the evolution of language. We believe this change serves those ends.”

Thank you, AP – we can all use a bit more inclusivity and respect in our lives!

Diallo

Founder, LOQUATIO

Does AI in Thought Leadership Represent a Race to the Bottom?

April 25, 2024

I’m the first to admit that I don’t have the answers to all the mysteries of the universe. But when creating public-facing white papers, research, commentaries, and other forms of content, I definitely have some concerns.

0 Comments6 Minutes

Is Meritocracy a Myth?

November 14, 2023

The New York Times recently published an article, Stuyvesant High School Admitted 762 New Students. Only 7 Are Black.

0 Comments4 Minutes

Reflections on the Civil Rights Movements, Photos, and My Dad

September 24, 2022

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, the African American community fell into a collective state of mourning - but not necessarily disbelief.

0 Comments2 Minutes

Optimific: Ethics in Content Creation

Journalists have always been well versed in the importance of ethics. But when you sit on the other side of divide, and your work is intertwined with sales...where do you draw the line?

For decades, creating content has been a “thing”, often without glamour or glitz. In the 1990s, if you worked within a major organization as an editor or copy editor, for example, that was NOT considered sexy by any stretch of the imagination. But those of us who created content had a little secret — the work was intellectually stimulating and our skills were always in demand. Further, the pay was respectable, we maintained a great quality of life, and we flew just below the radar…which allowed us to avoid the political infighting.

The cool factor and ethics

Today, with conferences on creating content and cool sounding names like “content marketing” and “chief content officers,” the jig is up — content creation has become a “new, bigger thing”. Even journalists, who once got more cool points than us back office mopes, are crossing over to the “dark side.”

And like all “new, bigger things”…the attendant new and bigger problems arise. One such problem that doesn’t get the attention it deserves is the challenge of maintaining ethical standards. Journalists have always been well versed in the importance of ethics. But when you sit on the other side of divide, and your work is intertwined with sales…where do you draw the line?

Promoting the greatest good

In the coming weeks, we’ll explore the issue of promoting ethical decision making when creating content. But for starters, let’s consider one of my favorite words — one that nobody ever seems to know (even my old Lit professor) — “optimific”. The term “optimific” is used in the world of philosophy to mean “that which promotes the greatest good.”

Consider it a sort of moral evaluation. For instance, how do you measure the “goodness” of something?

Philosophers like Immanuel Kant argued that certain rules are inviolable, such as respecting humanity. On the other hand, hedonism sets the ethical bar much lower, valuing that which produces the most pleasure.

Meanwhile, two of my favorite philosophers – Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mills a.k.a. proponents of utilitarianism – focus less on the intent and more on the outcome. Utilitarianism would ask us to consider the degree of “good” produced versus the “bad”. That’s where the term “optimific” enters the equation. Which act promotes the greatest good?

A practical example of this is when a company’s white paper is really a camouflaged product brochure. Are native advertisements looking a wee too similar to editorial content? And of course, there’s no shortage of media outlets willing to print “stories” (quotes intentional) designed for the sole purpose of triggering base human emotion rather than informing their audience.

Most organizations claim they draw a clear line when it comes to their standards in creating content. Regrettably, that line can quickly vanish when dollars are on the table.

Utilitarianism and creating content

Now back to our word of the day. Within utilitarianism, there’s act utilitarianism, which focuses on “acts” that promote good. For example, is it wrong to take the organs of a living person to save the lives of four other people? Or think about an example that is closer to home (unless you’re actually involved in harvesting organs): Should your thought leadership content promote your company’s products and services? Or should it focus on issues that executives in your industry truly care about?

Meanwhile, rule utilitarianism considers “rules” that yield the greatest good. For you organ harvesters out there, imagine how fragile society would be if randomly killing healthy people was permissible.

And for those of us involved in content, are those “Best of… Lists” really the “best”? Should big advertisers be afforded greater access to editors, and enlisting them to speak at events? Ultimately, rule utilitarianism asks that we think about what is optimific for society over the long term.

The happy pig

The moral imperative for content creators is this: rather than allowing the loudest voice, dollars and cents, or keeping up with the competition to be our compass when creating content, we should rely on an optimific set of criteria. I know this can be easier said than done. But when you find yourself in an ethical quandary, channel your inner John Stuart Mill:

“It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of different opinions, it is because they only know their own side of the question.”

Does AI in Thought Leadership Represent a Race to the Bottom?

April 25, 2024

I’m the first to admit that I don’t have the answers to all the mysteries of the universe. But when creating public-facing white papers, research, commentaries, and other forms of content, I definitely have some concerns.

0 Comments6 Minutes

Is Meritocracy a Myth?

November 14, 2023

The New York Times recently published an article, Stuyvesant High School Admitted 762 New Students. Only 7 Are Black.

0 Comments4 Minutes

Reflections on the Civil Rights Movements, Photos, and My Dad

September 24, 2022

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, the African American community fell into a collective state of mourning - but not necessarily disbelief.

0 Comments2 Minutes

Write Like The Economist

Why you should never sacrifice your brand, always write without pretension, edit until every word has its place, and commit yourself to serving your readers first.

News organizations have taken a beating over the years. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the newspaper publishing industry cut over 50% of its staff from 412,000 in 2001 to 174,000 in 2016. One bright spot is that Internet publishing has helped those media companies willing to make the leap, with employment jumping from 67,000 jobs in the beginning of 2007 to 206,000 in September 2016.

But at LOQUATIO we are more concerned that the proliferation of “more” content has not necessarily translated to “better”. The term “fake news” has become a part of our collective vocabulary; and digital platforms are struggling to protect their audiences from misinformation. In fact, this reckoning has left us with at least one undeniable fact: your ability to create high-quality content matters more than ever. And while no single media brand holds the patent on quality, there are a host of nuggets content creators can unearth from the shards and rubble of the news industry.

The Economist

The Economist is a bit of a black box. There are no bylines. There are no celebrities, with perhaps the exception of a few noteworthy editors. The magazine (or “paper,” as it is called) eschews periods in prefixes (i.e., Mr, Ms, Dr, etc.) and has little use for the letter “z”. These quirks, notwithstanding, the paper is a global brand that continues to inspire respect and admiration.

There are already articles and blogs galore about its writing style. Here is one Quartz article about The Economist versus Bloomberg. Here is another link to The Economist style guide if you are so inclined.

Perhaps the occasional wry joke or witticism makes for an entertaining read. But most of the musings about The Economist’s style, in my humble opinion, miss something very important—namely, the esprit de corps that everyone at The Economist shares.

The brand bank

During my first month at the Economist Intelligence Unit working on thought leadership projects, we got an introductory lecture from Andrew Rashbass, then-publisher of The Economist. He would rhetorically ask, “If we think of The Economist brand as a bank, are we making deposits or withdrawals?”

At The Economist, you must be “brilliant”. And The Economist attracts brilliant people by the droves. The fact remains that no one can be brilliant every hour of every day. Still, you are keenly aware that what you do has a bearing on the brand. Legal, operations, IT, editorial, sales, and everyone else who works at The Economist understands they matter—and that they contribute to the success of the brand. To the chagrin of some of the sales team, we would turn away projects if they jeopardized brand integrity. (Buy me a drink one day and ask about Time Inc., on the other hand.)

Journalism versus analysis

There are countless ways to slice and dice the field of journalism. There is print journalism, investigative, broadcast, features, and the list goes on. However, as Anna Szterenfeld, a former editor at The Economist Group who specialized in business intelligence and risk for Latin America, reminded me: there is a difference between what The Economist does and pure journalism.

Anna rightly points out that The Economist does not specialize in breaking news stories. The Economist is more analytical. “You never insult the intelligence of the reader or dumb down information,” she says. “But you also want to ensure that readers clearly understand issues in a new way. It is a fine balance.”

My then-boss would often say, “If we are saying the same thing as everyone else, then we are not providing any value.” Does the world need another article about how the coronavirus emerged from China? Or perhaps an analysis of the economic impact of the virus is more fitting? Rather than printing a laundry list of the “who’s who” and “what’s what” from Davos, why not ask whether the World Economic Forum is even relevant today?

Editing to make every word count

Another way we aimed to create high-quality content was through relentless editing. I would occasionally gripe (in private, of course) that if an editor from The Economist got their hands on the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, they would criticize it for being redundant for saying, “I have a dream,” too many times.

The editing process does, however, force you to ask the question: “Does each word matter?” Or as George Orwell wrote in “Politics and the English Language”:

“A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus: What am I trying to say? What words will express it? What image or idiom will make it clearer? Is this image fresh enough to have an effect? And he will probably ask himself two more: Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?”

Avoid pretension

If you have managed to read this far, then I have done my job.

Hopefully this serves as a reminder to everyone involved in creating content: You have an obligation to your audience—to inform, not impress. People should feel as though they know more about our world after reading your work. If they become impressed as well, let that be purely coincidental. In other words, to write like an editor from The Economist, never sacrifice your brand, write without pretension, edit until every word has its place, and commit yourself to serving your readers first…and your ego last.

Does AI in Thought Leadership Represent a Race to the Bottom?

April 25, 2024

I’m the first to admit that I don’t have the answers to all the mysteries of the universe. But when creating public-facing white papers, research, commentaries, and other forms of content, I definitely have some concerns.

0 Comments6 Minutes

Is Meritocracy a Myth?

November 14, 2023

The New York Times recently published an article, Stuyvesant High School Admitted 762 New Students. Only 7 Are Black.

0 Comments4 Minutes

Reflections on the Civil Rights Movements, Photos, and My Dad

September 24, 2022

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, the African American community fell into a collective state of mourning - but not necessarily disbelief.

0 Comments2 Minutes

Get the Most out of Your Marketing Efforts with Clear Language

We analyzed the top 100 asset management firm websites for readability. Among the 80+ websites that we scanned, we came away with some interesting findings.

In the mid-1990s, I stumbled upon a career as a financial editor. After starting at an investor relations consulting firm, I eventually went to work with Standard & Poor’s. I still remember my first high-level meeting (which, in retrospect, might not have been that high profile). This was an opportunity to rub elbows with the movers and shakers.

One of the managing directors ran the meeting. He and I always exchanged pleasantries—and I looked forward to seeing him in action. Was I impressed? Befuddled, perhaps. Confused, absolutely. He was speaking in English and I understood each word in isolation. But the way he structured his sentences left me bewildered. Words like synergy, integrated, leverage, etc. all have vague meanings, and were even more vague on that fateful day.

Over time, it became apparent that this wasn’t an isolated incident. Rather, there seemed to be an unspoken rule in the financial services industry that complex language makes you sound smart. For example, who could forget (or even understand) Alan Greenspan’s 1996 “irrational exuberance” quote:

“But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?”

The above requires you to read at a grade level of 17.6. In other words, he was speaking to someone in his or her last semester of getting a master’s degree.

Even though this unfortunate trend of using complex syntax continues today, the reality is that rather than impressing people, it has the opposite effect. Just ask Daniel M. Oppenheimer. He’s a former Princeton University professor who won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Literature for his ironically titled paper, “Consequences of Erudite Vernacular Utilized Irrespective of Necessity.” Among other things, he discovered that needless complexity in language creates a negative impression among your audience rather than a favorable one.

Fast forward to today. With the massive shift toward mobile technology and digital advertising, many asset management firms are revolutionizing how they engage with their clients. In our report, we’ve explored how effectively the asset management industry is using language as part of its marketing efforts. Using Clarity Grader, a proprietary tool created by Visible Thread, we’ve scanned the websites of the world’s largest asset management firms. We then created the Visible Thread/LOQUATIO asset management index based on characteristics such as readability, passive language, sentence length and complexity. The findings are interesting—and also instructive for asset management firms that want to strengthen their brands and gain the public’s trust through clear language.

To receive a copy, please drop us a note here.

“But how do we know when irrational exuberance has unduly escalated asset values, which then become subject to unexpected and prolonged contractions as they have in Japan over the past decade?”

Does AI in Thought Leadership Represent a Race to the Bottom?

April 25, 2024

I’m the first to admit that I don’t have the answers to all the mysteries of the universe. But when creating public-facing white papers, research, commentaries, and other forms of content, I definitely have some concerns.

0 Comments6 Minutes

Is Meritocracy a Myth?

November 14, 2023

The New York Times recently published an article, Stuyvesant High School Admitted 762 New Students. Only 7 Are Black.

0 Comments4 Minutes

Reflections on the Civil Rights Movements, Photos, and My Dad

September 24, 2022

When the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, the African American community fell into a collective state of mourning - but not necessarily disbelief.

0 Comments2 Minutes

Viewing Risk Management Through the Prism of Culture

Do cultural attitudes inform risk management practices across countries?

In the years since the financial crisis, financial (and non-financial) institutions face intense pressure to strengthen their risk management controls—but there are still questions about implementation. In my mind, one element of risk management that is too often ignored is the subjectivity of risk management. How strictly do firms actually adhere to the policies and procedures that they have in place? Is risk clearly communicated throughout the various layers of management, or is communication more relaxed? Furthermore, to what extent are attitudes toward risk management informed by cultural norms and biases in each firm’s home country?

U.S. financial regulators who examine a cross section of foreign banks with operations in the US often comment (albeit behind closed doors) how firms from different countries are likely to manage their risk in accordance with their cultural norms. For example, when a Japanese trading firm sets limits for traders, it may set the limit so high that a trader would never exceed it. While this may appear positive, from a regulatory perspective, limits that are set too high are effectively not limits at all. However, from the perspective of the risk manager, this high limit protects them from the appearance of a mistake, failure, or losing face (“kao”) by asking senior management for limit extensions. Losing “kao” or face in Japan can have disastrous consequences for a business relationship.

These observations are not intended to ascribe any value to culturally informed attitudes towards risk management. Instead, should we examine the different ways in which cultural norms may (or may not) be expressed through risk management?

For example, Dutch social psychologist Geert Hofstede developed a Power Distance Index that measures hierarchy within a particular society. According to Hofstede, hierarchy influences how problems are communicated, shared, and resolved. In countries ranking high on the Power Distance Index, there tend to be greater hierarchy and reluctance to report problems to senior management. Conversely, countries ranking lower tend to exhibit power relationships that are more consultative.

If you have thoughts on this, we’d love to hear from you.

A How-To Primer on Thought Leadership Surveys

The term “thought leader” is bandied about so much these days that it runs the risk of being relegated to the “jargon graveyard.” Just look at some of the recent headlines:

Financial Times: Stop thought leaders from turning useful ideas into pap Inc.: Here’s How to Build a New Career as a Thought Leader Nasdaq: How to Position Yourself as a Thought Leader in the ETF Space

Maybe we should start by being completely transparent. When I see these headlines, I also roll my eyes… But don’t lose hope!

The explosion in content marketing shops, online tools and events would make you think creating insightful content was something new. But the reality is that sharing business insights is a long-standing tradition—with no signs of abating. In fact, thoughtful content that helps improve our understanding of the world is arguably even more important today than ever before.

Having been involved in developing reports for the likes of Standard & Poor’s, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, etc., and creating Fortune’s first thought leadership business, I figured I’d take a minute to share my thoughts about thought leadership (no pun intended) and, more specifically, survey-based studies.

No, It’s Not That Simple

With cheap, online survey vendors at your disposal, creating a survey can seem simple—so much so that even a grade schooler can do it. After all, how much effort goes into creating a five-question survey that makes you think you’ll win a new iPhone?

My goal today is to dispel the notion that creating thought leadership surveys is just as simple. And below is a primer to help you think through creating your next (or very first) thought leadership study.

Understanding the Difference between Market Research and Thought Leadership

First, I cannot emphasize enough that there’s a distinct difference between consumer/market research studies and thought leadership studies. Does your company create flavored water, for example? If you want to conduct a study about consumer preferences, that’s absolutely fine. Generally, with such studies, people are compensated for their time and the purpose is clearly stated. Further, under these circumstances, it’s quite acceptable to ask people questions about your product or service.

On the other hand, a thought leadership study is generally directed to senior-level executives about their perspectives on issues affecting their business. Their time is valuable; and they aren’t participating because they want to talk about your business. Instead, the issue that you’re exploring should resonate with the particular demographic you’re surveying.

The takeaway: Please fight the temptation to create a self-serving survey.

This can be challenging when marketing dollars are tight, and you’re pressured to quickly demonstrate the ROI of a survey or white paper. And that’s why conducting thought leadership studies might not be the right fit for every organization.

Does your organization value thought leadership (as opposed to consumer studies/market research)? If you’re more focused on clicks, likes and re-tweets, then thought leadership studies may not be the right choice for your business. You can certainly get a lot of exposure via social media for your work. But the survey should be part of your broader strategy to engage business executives within your industry. Please know that I’m not saying this to sound boorish. I want to set you up for success, not failure. The fact of the matter is that surveys can be more time-consuming and expensive than your boss may realize. That’s why it’s important to manage expectations from the outset.

Here’s another reason you want to avoid a survey that’s too self-serving: What if the respondents don’t like your product or service? Is that a finding that you really want to broadcast? Or how will the higher ups feel about spending all that time and money, only to be left with findings that they’d rather not see the light of day?

Granted, some companies will conduct market research for their own products, and then pass it off as thought leadership. It may get a little attention – but people who are serious about their work will recognize the difference.

Finding Your Focus

When developing a survey, how do you focus on what matters to your audience? One way to approach this may be to think about a hypothesis. In other words, what do we want to test? Let’s say your business supports financial services firms. Your hypothesis may be that more mature companies are better at navigating regulatory minefields. Consequently, you may want to explore how companies of differing sizes and maturity levels are dealing with regulatory complexity.

Why would you chose a topic like this? For starters, you’re helping firms benchmark themselves against industry peers. Also, you’re demonstrating that you understand and care about how regulatory complexity can affect firms. And when you’re talking to subject matter experts, what do you think will resonate more?

“Here’s a study about how great we are.”

Or

“Here’s a forecast about the future of our industry.”

Over the years, we’ve done surveys on risk management (for management consulting firms), cross-border M&A (for law firms), pharmaceuticals in China (for a healthcare CRO), IT-related reputational risk (for a tech firm), and the list goes on… As you see, these topics were related to the sponsor’s business—BUT they were not about the sponsor’s business. Do you see the difference?

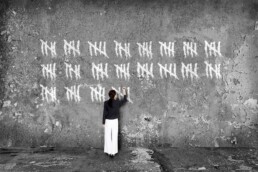

Survey Design

Now that we’ve sorted out the topic, let’s look at the actual survey design. This can be a tricky process, as there’s often the tendency to throw everything—including the kitchen sink—into the survey. I once worked with an organization that wanted to ask over 60 questions. Are you interested in filling out a 60-question survey? Most of us would rather have our teeth cleaned. (I actually like my dentist, but that’s beside the point.)

I know this also requires restraint, but for your own sake, fight the temptation to boil the ocean with your survey. Your respondents will appreciate a concise, thought-provoking survey more than a meandering one that wastes their time. And by “appreciate,” I mean “finish.” (Note: In most survey platforms, if the respondent doesn’t hit the submit button at the end, their responses aren’t recorded.)

To help you become a lean, mean survey machine, there are some best practices when it comes to design—most of which will help you avoid respondent drop off (i.e., someone starts and decides they don’t want to finish) and to get quality responses (i.e., survey takers provide honest and informed responses rather than random feedback).

For surveys of executives, we generally want to limit the length to 25 questions—including five demographic questions (e.g., company size, industry, level of seniority, etc.). You may also find it helpful to think about dividing your survey into sections—which can help you cover more territory. For example, you can ask about “today’s challenges,” “future opportunities,” “potential roadblocks,” etc.

The actual questions should be easy to answer as well. This may sound self-evident, but I’ve seen companies pose some questions that were problematic, such as asking respondents to rank their “top three” out of 20 choices. On the face of it, this looks like a straightforward question. But the fact of the matter is that not only are you asking a busy executive to wade through 20 different options for one question, you’re also asking her or him to rank them. These types of questions only increase the cognitive burden on your respondents and the likelihood of drop-off, while not providing you with any real benefit. (Note: Once you aggregate the responses and begin analyzing the results, you’ll see which answer choices were selected most—but not necessarily which ranked as #1, #2, or #3.) There’s so much more to say about the actual questions, but I’ll save that for another time.

Executing Your Survey

If you have a simple survey, online platforms like SurveyMonkey may do the trick. However, if your survey is more elaborate and you need to reach a specific demographic because you’re publishing the results, we suggest working with a survey vendor. The benefit here is that you can select the survey demographics – such as number of respondents, industries, titles, etc., and the survey vendor will access the appropriate panels to ensure they get the responses for you. Or firms like the Economist Intelligence Unit, The Economist’s business intelligence unit, have their own proprietary panels. So rather than you asking people you know to take the survey (which really doesn’t work), the survey vendor will ensure that you get the responses you need in approximately two to three weeks.

Survey Analysis

O.k., your survey is complete. Now what? This is where the magic happens. Analyzing a well-designed survey is really fun, particularly when you can unearth surprising trends. To get the most out of your survey, you should have someone help you who is familiar with analyzing the data. You may be good with numbers, but you’ll want someone who is familiar with conducting cross-tab analysis and working with programs like Tableu.

For example, you may want to explore how CEOs answered a particular question relative to director-level executives. Or perhaps you’ll want to compare responses across regions. How do executives in Asia think about the future of their business versus North America? And of those in North America who are bullish on the economy, what percentage are also concerned about a decline in revenue? You get the picture…

Costs

Lastly, one of the most important considerations: Costs. The more senior and idiosyncratic the audience you’re looking to reach, the higher the costs. To illustrate, I once did a survey of executives who were director-level and above, and whose companies were involved in cross-border mergers & acquisitions. They also had to be domiciled in one of the following countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Turkey. Suffice it to say, this was a low six-figure survey.

Conversely, I did a digital marketing study purely as a lead gen tool when we didn’t have much of a budget. I decided to poll executives who had “been involved in the marketing of their companies,” regardless of title or industry. This opened up the playing field and kept the costs to under $10,000.

Now You’re on Your Way

Surveys can be fun (coming from someone who once thought they were stupid). But they can also be a complicated undertaking. With myriad stakeholders wanting to provide input (while not fully appreciating the complexities), it’s easy to see how an organization can get lost in the minutiae—and ultimately undermine its efforts to launch a successful survey. Hopefully, the above helps you avoid some landmines. And of course, if you want to chat about this in more detail, just let me know—I’m easy to track down.

The takeaway: Please fight the temptation to create a self-serving survey.